Partnerships are often praised in glossy reports, signed at launch events, and toasted at stakeholder meetings. But when the cameras switch off and field boots replace suits, that’s when the real story begins. That’s where CIMMYT’s partnership with Total LandCare (TLC) in Malawi comes into focus, not as checkbox collaborations, but as hard-won relationships forged over decades of trial, error, and sheer persistence.

Since 2005, CIMMYT and TLC have steadily built a partnership rooted in scientific integrity and local trust. Together, they have championed conservation agriculture (CA) and sustainable intensification (SI) in Malawi, not just as theoretical ideals but as lived practices reshaping farming landscapes. At the core of their partnership lies a shared commitment to improving maize-legume systems and unlocking insights that matter to farmers, from higher yields, healthier soils, and more climate-resilient livelihoods.

Conservation agriculture has long been promoted as a pathway to climate-resilient farming in Malawi. And for good reason. A growing body of peer-reviewed studies, led by CIMMYT and local partners like TLC, offers strong evidence that CA works if rooted in local realities. The research is rigorous, often spanning a decade or more, and grounded in on-farm trials with smallholder farmers across Malawi’s diverse agroecologies.

When science is grounded in farm realities

Early research by Ngwira et al. (2013) demonstrated that multi-year CA trials in maize-legume systems maintained or improved grain yields over time. Notably, crop rotations performed better agronomically and economically than conventional ridge tillage, proving that no tillage, crop diversification, and residue retention pay off.

Another long-term study by Thierfelder et al. (2013) showed that CA practices in southern Malawi led to gradual yield increases, improved soil moisture, and stabilized yields, particularly in dry years.

Further analysis by Komarek et al. (2021), combining long-term trial data with climate simulations, found that CA systems buffered maize yields under drought and heat stress—a critical insight as Malawi faces more variable rainfall in recent years. Their findings supported Malawi’s inclusion of CA in its climate-smart agriculture strategy, showing that long-term yield stability is possible when science aligns with local implementation. But even the best science can’t scale alone!

Scaling influence

In conservation agriculture (CA), scale doesn’t come by magic; it grows through sweat equity, local trust, technical rigour, and sometimes honest disagreement. CIMMYT’s conservation agriculture journey with TLC started in 2005 in the Nkhotakota district, targeting just six farmers in each of the Mwansambo and Zidyana Extension Planning Areas (EPAs). Despite agronomic benefits, the adoption of conservation agriculture by Malawian smallholders has been modest and geographically uneven. In some cases, some farmers gave up along the way, while others kept going.

Earlier research by Ngwira et al. (2014b) surveyed 300 smallholders in southern Malawi (Mpatsa Extension Planning Area in Nsanje district) and found just 10% had fully adopted all three principles of CA. Labor burden, land constraints, and knowledge gaps held others back. Over time, deeper research revealed something more important on retention beyond just initial adoption. Pangapanga-Phiri et al. (2024) studied a “CA sentinel site” in Nkhotakota, where CA had been promoted for over a decade. Even after project support scaled down, 57% of farmers were still practicing CA for at least five consecutive years on the same plots, showing evidence of sustained use.

What made the difference? Tangible yield benefits, consistent extension support, and trusted local champions (experienced “lead farmers”) who modelled CA in practice, not theory. Still, even in this success story, dis-adoption remained a challenge. The study also noted that about 40% of initially enrolled farmers eventually abandoned CA on some fields, often citing that “CA is labor-intensive” or that promised yield gains did not materialize quickly enough. CA, for all its promise, is not a one-size-fits-all solution, and should be tailored to farmer needs.

Slow wins, deep roots

“From the beginning, adoption wasn’t good,” Richard Museka, project manager from TLC, recalls. “Farmers were scared. But now, in areas like Mwansambo, more than 57% of farmers practice CA. It has taken time, and we’re still building, but it’s working.”

Innovation is essential in tackling tough trade-offs in Malawi’s mixed crop-livestock systems: from residue burning on huge tracts of land for protein sources like mice, to competition for crop residues needed for soil cover and dry-season grazing, and labor-scarce households which lack uptake by youth can make CA appear too demanding. And not all farmers adopt at the same pace. “There are always slow uptakers,” Museka notes. “But they eventually come around when they see who’s thriving.” In some cases, some farmers adapt creatively, replacing maize stover with alternative mulching materials more suited to local conditions. In Mwansambo, farmers use groundnut shells and thatch grass to protect their soils, reducing pressure on residues typically left in the field.

This journey didn’t follow a linear path. There were setbacks, from weather shocks to leadership gaps following the death of key local champions. Some fields flourished while others failed. Their partnership proved steady with years of collaboration across multiple initiatives, even in tough times. “We have faced good and bad things together. Even when CIMMYT didn’t have enough funding, we could jump in and support the trials,” says Museka. That mutual support laid the foundation for something lasting. They have built a resilient learning network of farmers, researchers, extension agents, and input suppliers united not by flawless implementation, but by curiosity, commitment, and course correction.

Under the CGIAR Scaling for Impact initiative, with CIMMYT implementing the scaling research component for advancing CA, it’s the combination of CA and maize that’s caught the most traction, particularly in this maize-rice prioritizing region. The results are even better where legumes are rotated in, especially groundnut. Yet, despite visible success, not all farmers immediately adopt CA. But again, this isn’t a story of neat success. It’s a story of holding space for slow wins, of losing farmers to disinterest or generational shifts, and learning that succession planning is just as important in rural communities as letting a long-term trial die a natural death. It’s a story of seeing promising plots like the ones in central Malawi—rich, healthy, and productive—and asking why they’re not being copied across the board.

The answer? Scaling is messy. It requires more than a demo plot. It demands patience, learning loops, localized adaptation, behavioural, and institutional change. There is still much to do, especially around developing output markets that match the gains in input access and production. But the foundation is solid, from relationships that have stood the test of time, technical knowledge evolving with the climate, and farmers whose lived experiences continue to shape the science.

Building on other successes

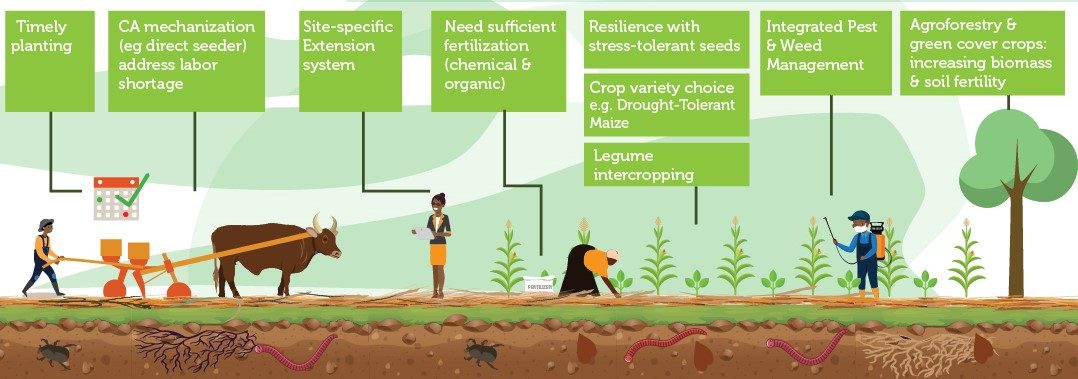

CA in Malawi doesn’t stand alone. It is part of a broader sustainable intensification strategy, integrating crop diversification, improved seed, appropriate-scale mechanization, and soil fertility management.

CIMMYT-led studies, including those under the SIMLESA project, tested combined approaches. The data show that CA delivers the most significant returns with practices like maize-legume rotations. Pigeon pea and groundnuts break pest cycles, add nitrogen, lift yields, and improve soil health. Building on the previous collaborations, TLC remains a partner of choice on new initiatives, including the Southern Africa Accelerated Innovation Delivery Initiative (AID-I) Rapid Delivery Hub.

So yes, partnerships matter—but not the kind you list in reports. The kind that shows up year after year and doesn’t give up, evolves with the seasons, and doesn’t flinch when things go wrong; that builds trust, field by field.

This is how change takes root.

And that’s how CIMMYT, TLC, and partners across Malawi are doing the work—quietly, patiently, relentlessly.

Sources:

- Ngwira, A.R., Thierfelder, C., & Lambert, D.M. (2013). Conservation agriculture systems for Malawian smallholder farmers: long-term effects on crop productivity, profitability and soil quality. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 28(4), 350–363

- Ngwira, A.R., Aune, J.B., & Thierfelder, C. (2014a). DSSAT modelling of conservation agriculture maize response to climate change in Malawi. Soil & Tillage Research, 143, 50–58 (article no. 50)

- Ngwira, A., Johnsen, F.H., Aune, J.B., Mekuria, M., & Thierfelder, C. (2014b). Adoption and extent of conservation agriculture practices among smallholder farmers in Malawi. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 69(2), 107–119

- Thierfelder, C., Chisui, J.L., Gama, M., Cheesman, S., Jere, Z.D., Bunderson, W.T., Eash, N.S., & Rusinamhodzi, L. (2013). Maize-based conservation agriculture systems in Malawi: Long-term trends in productivity. Field Crops Research, 142, 47–57

- Komarek, A.M., Thierfelder, C., & Steward, P.R. (2021). Conservation agriculture improves adaptive capacity of cropping systems to climate stress in Malawi. Agricultural Systems, 190, 103116

- Pangapanga-Phiri, I., Ngoma, H., & Thierfelder, C. (2024). Understanding sustained adoption of conservation agriculture among smallholder farmers: insights from a sentinel site in Malawi. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 39(1), e10 (15 pages)

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation