Food security is at the heart of Africa’s development agenda. However, climate change is threatening the Malabo Commitment to end hunger in the region by 2025, said Leonard Rusinamhodzi, a systems agronomist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center.

Food security is at the heart of Africa’s development agenda. However, climate change is threatening the Malabo Commitment to end hunger in the region by 2025, said Leonard Rusinamhodzi, a systems agronomist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center.

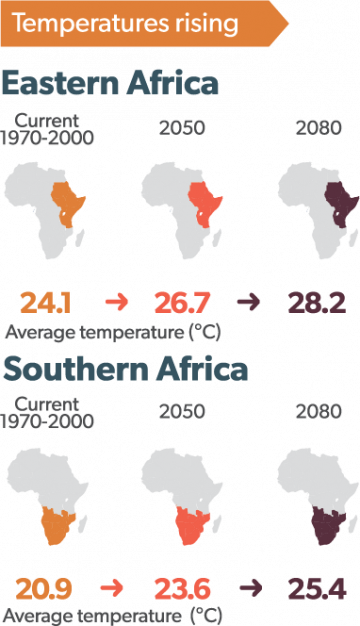

Erratic rainfall and increasing temperatures are already causing crops to fail, threatening African farmers’ ability to ensure household food security, he said. Africa is the region most vulnerable to climate variability and change, according to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Small-scale family farmers, who provide the majority of food production in Africa, are set to be among the worst affected. Rusinamhodzi’s work includes educating African farmers about the impacts of climate change and working with them to tailor sustainable agriculture solutions to increase their food production in the face of increasingly variable weather.

The world’s population is projected to reach 9.8 billion by 2050, with 2.1 billion people set to live in sub-Saharan Africa alone. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates farmers will need to increase production by at least 70 percent to meet demand. However, climate change is bringing numerous risks to traditional farming systems challenging the ability to increase production, said Rusinamhodzi.

Rusinamhodzi believes increasing farmers’ awareness of climate risks and working with them to implement sustainable solutions is key to ensuring they can buffer climate shocks, such as drought and erratic rainfall.

“The onset of rainfall is starting late and the seasonal dry spells or outright droughts are becoming commonplace,” said Rusinamhodzi. “Farmers need more knowledge and resources on altering planting dates and densities, crop varieties and species, fertilizer regimes and crop rotations to sustainably intensify food production.”

Growing up in Zimbabwe – a country that is now experiencing the impacts of climate change first hand – Rusinamhodzi understands the importance of small-scale agriculture and the damage erratic weather can have on household food security.

He studied soil science and agronomy and began his career as a research associate at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture in Zimbabwe learning how to use conservation agriculture as a sustainable entry point to increase food production.

Conservation agriculture is based on the principles of minimal soil disturbance, permanent soil cover and the use of crop rotation to simultaneously maintain and boost yields, increase profits and protect the environment. It improves soil function and quality, which can improve resilience to climate variability.

It is a sustainable intensification practice, which is aimed at enhancing the productivity of labor, land and capital. Sustainable intensification practices offer the potential to simultaneously address a number of pressing development objectives, unlocking agriculture’s potential to adapt farming systems to climate change and sustainable manage land, soil, nutrient and water resources, while improving food and nutrition.

Tailoring sustainable agriculture to farmers

Smallholder farming systems in Africa are diverse in character and content, although maize is usually the major crop. Within each system, farmers are also diverse in terms of resources and production processes. Biophysically, conditions – such as soil and rainfall – change significantly within short distances.

Given the varying circumstances, conservation agriculture cannot be promoted as rigid or one-size fits all solution as defined by the three principles, said Rusinamhodzi.

The systems agronomist studied for his doctoral at Wageningen University with a special focus on targeting appropriate crop intensification options to selected farming systems in southern Africa. Now, with CIMMYT he works with African farming communities to adapt conservation agriculture to farmers’ specific circumstances to boost their food production.

Rusinamhodzi’s focus in the region is to design cropping systems around maize-legume intercropping and conservation agriculture. Intercropping has the added advantage of producing two crops from the same piece of land in a single season; different species such as maize and legumes can increase facilitation and help overcome the negative effects of prolonged dry spells and poor soil quality.

“The key is to understand the farmers, their resources including the biophysical circumstances and their production systems, and assist in adapting conservation agriculture to local needs,” he said.

Working with CIMMYT’s Sustainable Intensification Program, Rusinamhodzi seeks to understand production constraints and opportunities for increased productivity starting with locally available resources.

Using crop simulation modeling and experimentation, he estimates how the farming system will perform under different conditions and works to formulate a set of options to help farmers. The options can include agroforestry, intercropping, improved varieties resistant to heat and drought, fertilizers and manures along with the principles of conservation agriculture to obtain the best results.

The models are an innovative way assess the success or trade-off farmers could have when adding new processes to their farming system. However, the application of these tools are still limited due to the large amounts of data needed for calibration and the complexity, he added.

Information gathered is shared with farmers in order to offer researched options on how to sustainably boost their food production under their conditions, Rusinamhodzi said.

“My ultimate goal is to increase farmers’ decision space so that they make choices from an informed position,” he said.

Rusinamhodzi also trains farmers, national governments, non-profit organizations, seed companies and graduate students on the concepts and application of sustainable intensification including advanced analysis to understand system productivity, soil quality, water and nutrient use efficiency and crop pest and disease dynamics.

Leonard Rusinamhodzi works with the SIMLESA project funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research and the CGIAR MAIZE program.

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation